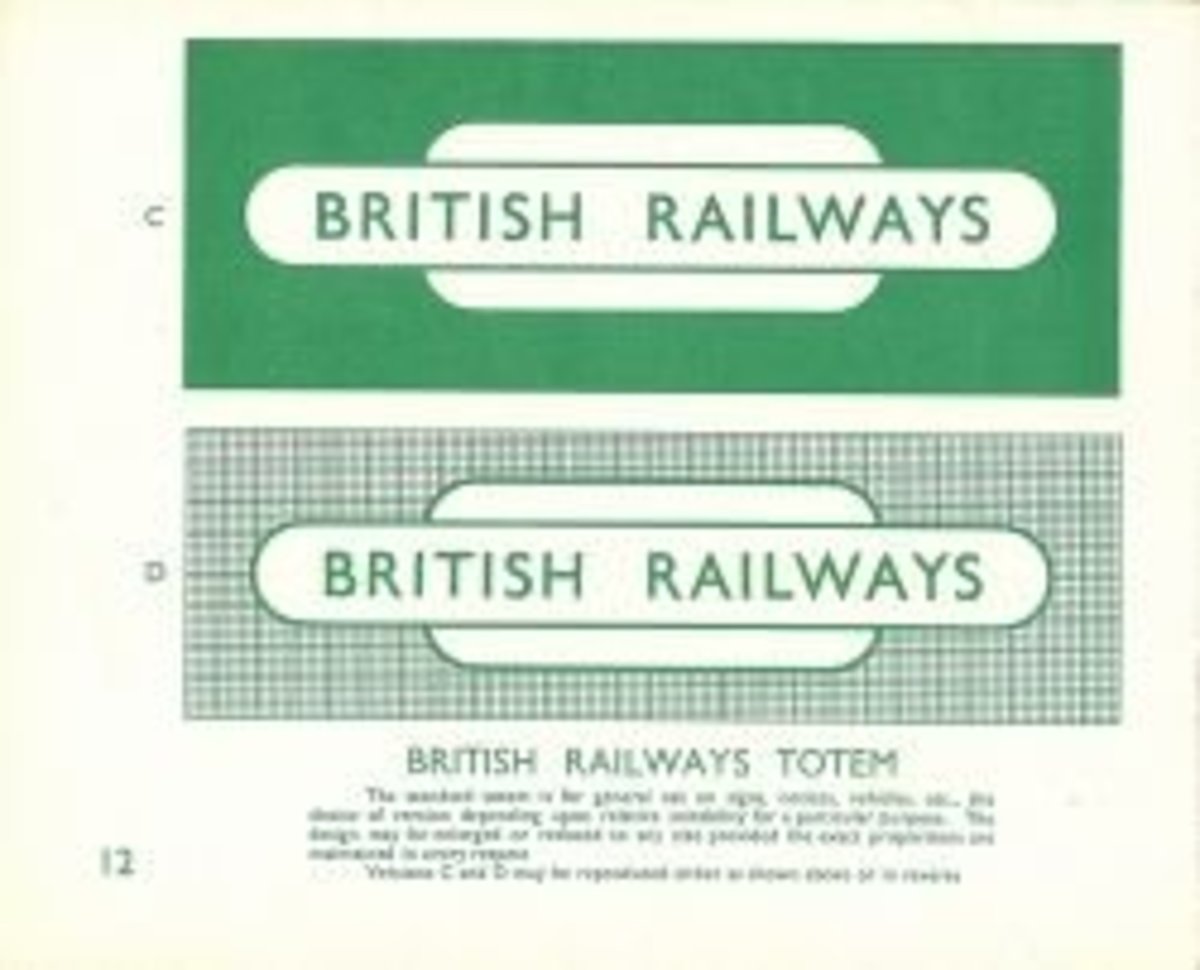

Licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence. ‘Totem’ sign at Barnstaple station, via here. The men in bowler hats expected you to bring a certain degree of intellectual application to the task at hand and certainly weren’t in the business of spoon-feeding you their instructions. And this was despite the fact (here comes one of the main reasons that I say Gill Sans is hard to work with) that the lower case ‘l’, upper case ‘I’ and numeral ‘1’ all looked identical. How reassuring it must have been for a train traveller of the 1950s to know that when arriving at Barnstaple, or looking for the Way Out, they could be in no doubt at all that they were indisputably at Barnstaple, or the Way Out would be precisely where indicated. As such, the signs were perfectly suited to the post-war period in Britain, the last time that men in bowler hats were in charge of everything, before the 1960s came along and the whole structure of society was blown apart. The British Railways station signs worked so well because Gill Sans is a very dictatorial font, ordering you about in a no-nonsense way. It’s also why there’s such a thriving auction business for the original totems and other station signage. This perfect marriage of font and sign design is why there’s a massive market in expensive bespoke replica station totems, and virtually no market in replica 1965-and-later station signs. By GearedBull at en.wikipedia, from Wikimedia CommonsIts use on British Railways signage, particularly the famous station “totems” (or “hot dog sausage signs” as they are unkindly referred to by philistines) arguably remains its best ever deployment, the typeface and the sign design working perfectly together (though the version on the signs is apparently fractionally different than standard Gill Sans, but not so much that anyone but a font enthusiast would notice I certainly can’t spot the difference). Then Gill Sans really spread its wings, because at nationalisation in 1948 it was adopted by the British Railways Board for its station signage, rolling stock lettering, timetables and publicity. Gill was a bit of an odd chap and some of his personal predilections aren’t suitable for a blog like this (so much so that there is occasional discussion of boycotting Gill Sans)¹…so let’s gloss over Gill himself and instead mention that the font’s first transport use was its adoption by the London & North Eastern Railway in 1929 as its official typeface for publicity and posters, later appearing on trains themselves.

Gill Sans was invented by Eric Gill in 1926, and released commercially two years after that. Despite the difficulties of using it, transport operators are compelled to return it again and again.

It is the ice maiden of transport fonts, beautiful but hard to work with. It possesses a chilly haughtiness and inspires fascination and devotion. Can there be a more seductive font in the realm of public transport than Gill Sans? While the response of most people when asked to think about a font used in transport will be to mention “the Underground signs” (Johnston, and latterly New Johnston on London’s Underground and other transport modes), it is Gill Sans which has had far wider use by transport operators.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)